The Mystery of the Lockdowns

In “How many lives would a more normal president have saved?” New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wonders how many Americans died because of President Trump’s “abnormal” reluctance to embrace stricter lockdown measures. Douthat’s speculations never get close to the likely correct answer, though, which is zero: a “more normal” president would have saved zero extra lives.

In “How many lives would a more normal president have saved?” New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wonders how many Americans died because of President Trump’s “abnormal” reluctance to embrace stricter lockdown measures. Douthat’s speculations never get close to the likely correct answer, though, which is zero: a “more normal” president would have saved zero extra lives.

That’s because recent studies find little evidence that differences in lockdown policies have had any effect on the pandemic.

It’s a mystery why governments were and remain eager to plunge along a path with such meager benefits to offset daunting costs. The costs include not only the worst world recession in modern times but also the emergency powers states have seized to enforce the lockdowns and the resulting loss of civil liberties by citizens.

The citizens’ loss has been the state’s gain. A new study finds that governments have declared emergencies mainly because of the new powers they stand to gain, not the severity of the pandemic.

Lockdowns and COVID

In “Did Lockdown Work? An Economist’s Cross-Country Comparison,” Christian Bjørnskov, professor of economics at Aarhus University in Sweden, looks at the association between the intensity of lockdowns and coronavirus deaths in 24 European countries.

Bjørnskov measures lockdowns with indexes of COVID policy that incorporate elements such as school closing, workplace closing, cancellation of public events, restrictions on gatherings, closing public transport, stay-at-home regulations, controls on internal movement, international travel controls, information campaigns, testing, and contact tracing.

He is also careful to address the “endogeneity problems” that afflict this sort of comparison. For example, we might underestimate how far lockdowns reduce COVID if, as seems likely, there is also “reverse causality,” with more severe COVID outbreaks causing governments to adopt more intense lockdowns. Countries also have features that affect COVID outcomes but that are hard to measure, for example, the extent of social cohesion and trust. If omitted from the analysis, these factors could also bias the estimate of how much lockdowns affect COVID. Bjørnskov tackles endogeneity problems using two different standard approaches, the “fixed-effects” and “instrumental variables” methods.

His findings?

“… more severe lockdown policies have not been associated with lower mortality. In other words, the lockdowns have not worked as intended.”

Another recent paper – “Four Recent Facts About COVID-19” – by Andrew Atkeson, Karen Kopecky, and Tao Zha of UCLA and the Federal Reserve comes to the same conclusion more indirectly. It analyzes statistical patterns in the growth of daily COVID-19 deaths through late July 2020 in some 23 countries and 25 U.S. states. Without getting into details, so similar are these patterns over time and across widely different countries and states that the authors question whether lockdown policies could have had any importance in the evolution of the pandemic.

The authors think earlier studies are likely to have overstated the impact of lockdowns on COVID-19 transmission because of an “omitted variable bias.” Among the potential omitted variables, perhaps the most important is the fact that, once a pandemic breaks out, rational, forward-looking humans spontaneously take action to avoid becoming infected. People slash their social and economic contacts whether or not the government has imposed a lockdown, leading to a rapid fall in disease transmission, as well as a deep but usually short-lived recession. (For discussion and evidence on this point, see, for example, here, here, or here.)

This sort of spontaneous or “private lockdown” occurring across all countries and regions could swamp the effect of government lockdown policies on COVID-19.

Lockdowns and the Economy

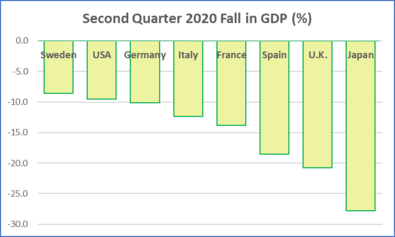

What about the economy? Numbers continue to roll in of staggering GDP declines in the second quarter of 2020. (Figure.) I’m not aware to date of any systematic cross-country studies that estimate the impact of the official lockdowns on economies. Failing such evidence, one can’t be sure how much official lockdowns have worsened recessions beyond what would have happened anyway due to the spontaneous, private efforts of people to avoid infection. But that worsening could be substantial.

A theoretical model by Eichenbaum, Rebelo, and Trabandt calculates that the official lockdown would more than triple the severity of the spontaneous or private recession – a 22% fall in consumption compared to 7% – even as it (in theory) reduces the transmission of the virus.

In Africa, whose young population means that relatively few are likely to die of COVID:

“A growing body of doctors, economists and scientists fear [the official lockdown] measures will have disastrous consequences. These experts warn of financial carnage, spiralling epidemics of other diseases, the intensification of gender and wealth inequalities and the battle against poverty being set back by decades.” (Ian Birrell: Africa’s catastrophic Covid response.)

Researchers estimate the lockdown will disrupt Uganda’s health care system so severely that a spike in HIV/AIDs, malaria, tuberculosis, and maternal deaths will exceed theoretical deaths from COVID-19 by a factor of at least two to one.

Lockdown Politics

How did countries make the momentous decision to shut down such vast – so-called “non-essential” – swathes of their economies, in many cases with still no end in sight? Politicians, desperate to fend off a potential public health disaster, say they took guidance from epidemiologists and other public health experts.

But “When and How Did the Experts Decide that the COVID-19 Pandemic Justified a Lockdown?” asks political scientist Larry Arnhart. There was, after all, no precedent in the world history of previous pandemics for any such policy. Nor can Arnhart find any evidence that experts in the U.S. ever conducted a cost-benefit analysis for lockdowns, setting their likely enormous economic and social costs against their public health benefits. Nor were the lockdowns based on the pandemic plans developed by earlier U.S. administrations.

The CDC’s 2017 pandemic guidelines, for example, insist on the need to balance economic and social costs against the public health benefits of pandemic actions. They mostly advocate social-distancing measures and nowhere, not even for the highest risk “Category 5” pandemics, do they support government-mandated lockdowns of “non-essential” sectors. The Trump administration’s March 2020 pandemic recommendations mainly followed this earlier guidance, giving the lead role to state and local governments.

Then, suddenly, mandatory lockdowns emerge as the one crucial way to fight the pandemic, championed by mostly Democratic state governments, “experts” in the federal health bureaucracy, and the mainstream media – all without a jot of evidence, analysis, or backing in earlier policy guidance. U.S. GDP fell by nearly 11% in the first half of 2020. Unemployment jumped to almost 15% in April.

It’s hard not to credit conservatives who say the lockdowns are at core political, aimed at disrupting a booming economy upon whose back Trump would otherwise have coasted to a comfortable election victory. More broadly, says Angelo Codevilla in “The COVID Coup,” they represent a counteroffensive by frightened “neoliberal” ruling elites – “Davos Man” – to knock away civil liberties and strengthen the power of the state over an increasingly restive citizenry.

Nutty right-wing conspiracy theories, you say?

Perhaps. But consider the recent cross-country study by Christian Bjørnskov and Stefan Voight: “This Time is Different? – On the Use of Emergency Measures During the Corona Pandemic.” By May 10 this year, 99 governments, almost half of all sovereign states, had declared a state of emergency due to COVID-19. States of emergency typically reduce civil liberties and increase the powers of the executive at the expense of other branches of government.

Bjørnskov and Voight study the factors that caused governments to declare states of emergency. Were governments motivated by the desire to save lives? Or by the opportunity to expand their powers? The authors create an index for the additional discretionary authority a government could gain by declaring an emergency, for example, by dissolving parliament, derogating from basic rights, confiscating property, or censoring the media.

Their conclusion:

“We find that the discretionary power [governments] gain during emergencies is the main determinant of whether they declared a state of emergency, while the severity of the epidemic is irrelevant. We also observe that the same governments are likely to misuse these powers against journalists and the media. The danger, as under previous disasters, is that some of the measures now implemented are likely to outlast the current pandemic and weaken the rule of law and democracies for many years to come.”

(Language edits, September 14.)